- Home

- Brian Wilson

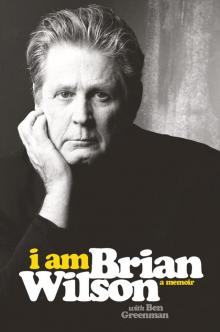

I Am Brian Wilson

I Am Brian Wilson Read online

Copyright © 2016 by Brian Wilson

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address Da Capo Press, 44 Farnsworth Street, 3rd Floor, Boston, MA 02210.

Designed by Jeff Williams

Set in 11 point Giovanni by Perseus Books

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: 978-0-306-82307-7 (ebook)

Published by Da Capo Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of PBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

www.dacapopress.com

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail [email protected].

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Melinda—

God only knows what I’d be without you

Contents

OVERTURE: Royal Festival Hall, London, 2004

CHAPTER 1: Fear

CHAPTER 2: Family

CHAPTER 3: Foundation

CHAPTER 4: Home

CHAPTER 5: Fathers and Sons

CHAPTER 6: Echoes and Voices

CHAPTER 7: Sun

CHAPTER 8: America

CHAPTER 9: Time

CHAPTER 10: Today

Discography

Acknowledgments

Credits

Overture

Royal Festival Hall, London, 2004

It’s been hard and it’s been easy. Mostly, it’s been both. My friend Danny Hutton from Three Dog Night recorded a song, “Easy to Be Hard,” that I sing to myself in my head sometimes: It’s easy to be hard, it’s easy to be cold. It’s cold now. It’s the winter of 2004 in London, and I’m getting ready to go onstage at the Royal Festival Hall. Some of the songs I’ll be singing are about the sun and the beach. There’s not much of either of those in London right now. But there’s water—the Royal Festival Hall is right on the river—and some of the songs are about that.

When I got here I was walking around and heard someone mention that the hall was originally built in 1949 but redone in the fall of 1964. That was a big year, 1964. It was the year of everything. The Beach Boys toured around the world. We were in Australia in January with Roy Orbison and all over the United States in July. They called that tour Summer Safari, and we played with people like Freddy Cannon and the Kingsmen. When we weren’t touring, we were recording: “Fun, Fun, Fun” and “The Warmth of the Sun” at the beginning of the year, “Kiss Me, Baby” at the end of the year, and more songs than you can count in between. We put out four records—three studio albums (including a Christmas one) and a live album. And that was on the heels of 1963, which was almost as busy—three albums and constant touring, too.

I don’t go back and listen to that old music very much. But I do think about it, and I try to imagine what was in my head back then. I can’t always get a clear picture. Sometimes it’s pieces of pictures. It’s hard to get back to where you were, you know? Over the years I’ve played new music and I’ve played old music. I’ve played both here at the Royal Festival Hall—my band and I came in 2002 to play Pet Sounds straight through, and people loved it. That was in summertime. Tonight is different, though. Tonight is the moment I have been dreading for months, and imagining for years. Tonight, in the second half of the concert, we’re playing SMiLE, the Beach Boys album that never was, for the first time. What the hell was I thinking? Why in the world did I think this was a good idea? SMiLE was supposed to be the follow-up to Pet Sounds back in the mid-’60s. It fell apart for so many reasons. It fell apart for every reason. Some of the songs that were supposed to make up SMiLE came out on other records over the years, but the real album went underwater and didn’t surface for decades. Finally I got back to it and finished it up. In my sixties I did what I couldn’t do in my twenties. That’s what has brought me to London this time.

I’m sitting out in the theater. Everyone’s getting ready. What brought me here to London? It’s hard to keep my train of thought. There are so many people going back and forth, so many musicians. I hear them tuning up or trading licks, but I also hear them talking, both the musicians here and other musicians from the past. I hear Chuck Berry, who was one of the first artists to turn boogie-woogie into rock and roll. What would Chuck have thought about all these strings and woodwinds? He probably would have walked right past them and gone onstage with a pickup band he hired when he rolled into town. I hear Phil Spector, who did all those great records in the ’50s and early ’60s. Phil’s voice is scary, always challenging me, always reminding me that he came first. “Wilson,” I hear him saying in my head, “you’re never going to top ‘You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling’ or ‘Be My Baby,’ so don’t even try.” But maybe he wants me to try. Nothing is ever simple with him, not when he’s in my head. Simple isn’t what he’s about. People say that we named Pet Sounds partly as a tribute to him: check the initials. I also hear my dad in my head. His voice is louder than the others. “What’s the matter, buddy? You got any guts? Is this all about you? Why so many musicians? Rock and roll is two guitars, a bass, and drums. Any more than that is just about ego.”

When I hear those voices, I try to shut them out. I’m just trying to get a feel for the room and how the songs will come alive inside of it. I’m also trying to get a feel for where I fit into all of this. Back in the old days with the Boys, I never liked going onstage. People used to write about how I seemed stiff. Then they started writing about how I had stage fright. It’s a weird phrase, “stage fright.” I wasn’t afraid of the stage. I was afraid of all the eyes watching me, and of the lights, and of the chance that I might disappoint everyone. There were so many expectations that I could figure out in the studio, but they were different onstage. A good audience is like a wave that you ride on top of. It’s a great feeling. But a crowd can also feel the other way around, like a wave that’s on top of you.

There are other voices, too, along with Chuck Berry and Phil Spector and my dad. The other voices are worse. They’re saying horrible things about my music. Your music is no damned good, Brian. Get to work, Brian. You’re falling behind, Brian. Sometimes they just skip the music and go right for me. We’re coming for you, Brian. This is the end, Brian. We are going to kill you, Brian. They’re bits and pieces of the rest of the people I think about, the rest of the people I hear. They don’t sound like anyone I know, not exactly, except that I know them all too well. I have heard them since I was in my early twenties. I have heard them many days, and when I haven’t heard them, I have worried about hearing them.

My whole life I’ve tried to figure out how to deal with them. I’ve tried to ignore them. That didn’t work. I’ve tried to chase them away with drinking and drugs. That didn’t work. I’ve been fed all kinds of medication, and when it was the wrong kind, which was often, that didn’t work. I have had all kinds of therapy. Some of it was terrible and almost did me in. Some of it was beautiful and made me stronger. In the end, I have had to learn to live with them. Do you know what that’s like, to struggle with that every single day of your life? I hope not. But many people do, or know someone who does. Everyone who knows me knows someone who does. So many people on the planet deal with some type of mental illness. I’ve learned that over the years, and it makes me feel less lonely. It’s part of my life. There’s no way aroun

d it. My story is a music story and a family story and a love story, but it’s a story of mental illness, too.

London is part of that story. I have often said that this city is my spiritual home. London audiences really appreciate my music. The SMiLE show is part of that story. It’s a way of bringing something back that looked like it would stay in the past. To calm myself, I try to meditate my way into the music. Music is the solution. Music takes what’s inside me and puts it into the world around me. It’s my way of showing people things I can’t show any other way. Music is in my soul—I wrote that once, and it’s one of the best lyrics I ever wrote.

I remember what I was thinking about: the past. Resurrecting SMiLE is both past and present. When we didn’t finish the album, a part of me was unfinished also, you know? Can you imagine leaving your masterpiece locked up in a drawer for almost forty years? That drawer was opened slowly. It came open a little bit at a Christmas party at Scott Bennett’s house, where I played “Heroes and Villains” on the piano, and then a little more when David Leaf told me to play it at a tribute show at Radio City Music Hall. And then it was pulled open almost completely by Darian Sahanaja. Darian is a singer and songwriter, just like me, except that he’s much younger, which meant that he loved the music we made but also had a new way of looking at it. He plays keyboards in my band and acts like a kind of musical secretary. At the Radio City show, which came a little after that Christmas party, my songs were performed by other people, like Paul Simon, Billy Joel, Vince Gill, and Elton John. Some were the big hits, but two were songs we had recorded for SMiLE, done the way we had originally imagined them. Vince Gill, Jimmy Webb, and David Crosby played “Surf’s Up” and the audience gave them—and the song—a long standing ovation. I couldn’t believe it. I was shocked. I was sitting on a stool at the side of the stage and David Crosby came off and said, “Brian, where did you come up with those fucking chords? They’re incredible.” I shook my head. “You know,” I told him, “I said goodbye to that song a long time ago.” Then I went out and played “Heroes and Villains” for the first time in more than forty years. I had promised at the party. The ovation was huge. The great George Martin introduced Heart, who played “Good Vibrations.” I couldn’t believe what he said about me, then and later on: “If there is one person I have to select as a living genius of pop music, I would select Brian Wilson. . . . Without Pet Sounds, Sgt. Pepper wouldn’t have happened. . . . Pepper was an attempt to equal Pet Sounds.” The producer of the Beatles said that about me—it was hard to even imagine. I was so honored.

After that, people started to ask if I would ever think about performing the whole album. I said yes. I was happy to say yes, but there are times, like now, when I’m not sure I was right to be happy.

I am sitting out here in the theater, meditating but not quite meditating. I’m aware of everyone going back and forth. At least a few of them want to stop and remind me about the way tonight’s show will work. I feel like I’ve been over it a hundred times. I know it backward and forward. We’ll start out with an acoustic set, then some material from my solo albums, then some early Beach Boys hits, then a few songs from Pet Sounds. Then there will be an intermission, and then the moment everyone has been waiting for—SMiLE, finally.

A guy stops near me and clears his throat. I look up. It’s Jerry Weiss, who has been my road assistant for years. “Hey, Brian,” he says. “They’re opening the doors now. Let’s go backstage.”

“Thanks,” I say. “Where’s Melinda?” Melinda is my wife.

“She’s in your dressing room. Let’s go there.” But I want to go to the band’s dressing room instead. That’s what you’re supposed to do before a show, at least after you try to find the vibe of the room. You’re supposed to be with the musicians and talk about the thing you’re about to make. I ask Jerry where the band’s dressing room is and he looks disappointed for a second but leads me to the band’s room anyway.

Darian is the first one I see. “Hi,” I say. “Do you mind if I sit here with you guys for a few minutes?”

“Of course not,” Darian says. “How are you feeling? Are you ready?”

“I’m ready,” I say. But because he asked, I tell him the truth also. “I’m a little scared and nervous. Do you think people will like it?”

“More than that. They are going to love it. You won’t believe how much. And then . . .”

Darian has crossed the room now and I can’t quite hear him. I am almost completely deaf in my right ear. It’s been that way since I was a kid. A professional musician who can’t hear on one side of his head? It’s funny but not funny. Over the years I have learned how to make it work in the studio, but it’s harder onstage, where you have to know what’s going on all around you. It’s hard to stay on key when you can’t hear everything that is being played. The sound up there can be overwhelming and I have only one monitor, to my left. It has to be positioned perfectly, just right, or all I can hear is noise. And of course there are these voices in my head. Sometimes they come with me onto the stage. Sometimes in the middle of a song I lose concentration because they are getting louder. Every time, I get through it. But then the next time, I’m not sure I will.

We’re ten minutes until show. Jerry tells me there are lots of people I know in the audience tonight. I ask where everyone is sitting. I want to be able to see them from the stage. That helps me with my nervousness, to know that the audience isn’t one big wave but lots of faces I already know. Melinda is sitting in the center, right in front of me. I will be able to look straight ahead and see her and feel her support. Jean Sievers, my manager, is right next to her; she helped get me here, too. Van Dyke Parks, who worked on SMiLE with me, writing lyrics, is also down in front with his wife, Sally. Roger Daltrey got to the theater early and came backstage to say hello. Wix and Abe from Paul McCartney’s band are down there. George Martin is down there. I’m thinking of all their faces and trying not to let the stage fright get to me. It surges and then goes back down. If I get used to the rhythm, I can make sense of it. Someone says something I can’t quite understand on my right side, and I turn so that my good ear catches it. “Time to go,” the voice is saying. “Time to go.” The lights go down and I hear the sound of the audience coming up.

CHAPTER 1

Fear

There’s a world where I can go and tell my secrets to

In my room, in my room

In this world I lock out all my worries and my fears

In my room, in my room

—“In My Room”

Mornings start at different times. In summer I wake up pretty early, sometimes as early as seven. It’s later in the winter—when the days are shorter, I sleep longer. I might not get up until eleven. Maybe that happens to everyone. It used to be worse. I used to have real trouble getting up in the winter, and even when I did, I might stay in bed for hours. These days it’s a little easier to start the day, no matter what the season.

When I wake up these days here in my house in Beverly Hills, I head down the back staircase to the den. That’s where the TV is, and also my chair. It’s a navy-blue print chair that’s been there forever. It used to be red. It’s been covered and recovered because I have a habit of picking at the upholstery. That chair is where I go when I come down from the bedroom. It’s my command center. I can sit there and watch TV, even though the set is at a little bit of a weird angle. I love watching Eyewitness News. The content is not very good, but the newscasters are pleasant to watch. They have nice personalities. They also give you the weather. I like game shows, but I am getting tired of watching Jeopardy! It’s the same bullshit every day. I like Wheel of Fortune. I like sports, too, mostly baseball, though I’ll also watch basketball and football. I get more interested toward the playoffs.

But the TV isn’t the only thing I can see from my chair. I can see into the kitchen and almost everywhere else. I can turn and look out the window and see into the backyard, which has a view of Benedict Canyon. The whole city’s stretched o

ut there if you go and look. And there’s a touch-tone phone right next to the chair so I can call whoever I want. I don’t use a cell phone. I have had a few over the years, but I don’t like them. I love being in the chair. If I’m in Los Angeles, I’ll end up there 100 percent of the days. If I come into the room and someone else is sitting in it, I just stand nearby until they clear out. When I go on the road, I take another chair with me, a black leather recliner, so that I can have the feel of home. I have them set it up on the wings of the stage and I sit there instead of in the dressing room.

Some people reach for coffee first thing in the morning. I don’t. I’m not a coffee drinker. That doesn’t mean that I’m alert on my own all the time, though. My nighttime medications make me drowsy, and it’s hard to get started. There’s a little hangover from the pills. When I get to the chair, I’ll sit there for half an hour or so. Then I’ll go out to the deli for breakfast. Breakfast has changed over the years. When I was less concerned about my weight, it might be two bowls of cereal, eggs, and a chicken patty. These days it’s a veggie patty and fruit salad or a dish of blueberries. Most mornings Melinda will come into the room, and she only has to take one glance to tell what kind of mood I’m in. She’s been with me long enough to know what the good moods look like, and what the other moods look like.

She doesn’t say anything in the mornings usually. She lets me sit. If the mood lasts until afternoon or evening, she’ll ask me about it. “What’s bothering you?” she’ll say. Usually it’s that I really miss my brothers. Both of them are gone—Carl for almost twenty years, Dennis for more than thirty. I can get into a space where I think about it too much. I wonder why the two of them went away, and where they went, and I think about how hard it is to understand the biggest questions about life and death. It’s worse around the holidays. I can really get lost in it. When it gets bad, Melinda sits near me and goes through the reality of the situation. She might remind me that Carl’s been gone for a while, and that even when he was alive, we didn’t spend so much time together. Toward the end of his life, we saw each other maybe once a year or so. “Of course you miss your brothers,” she’ll say. “But you don’t want to miss them so much that it puts you on a bummer.” And she’s right. I don’t.

I Am Brian Wilson

I Am Brian Wilson